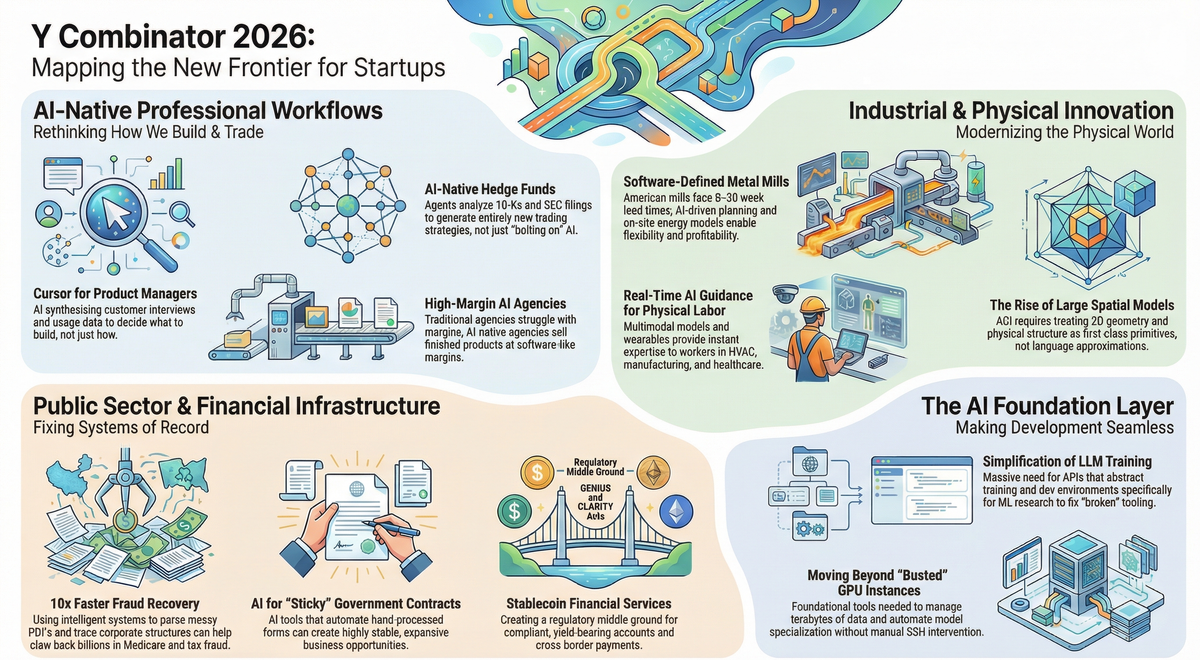

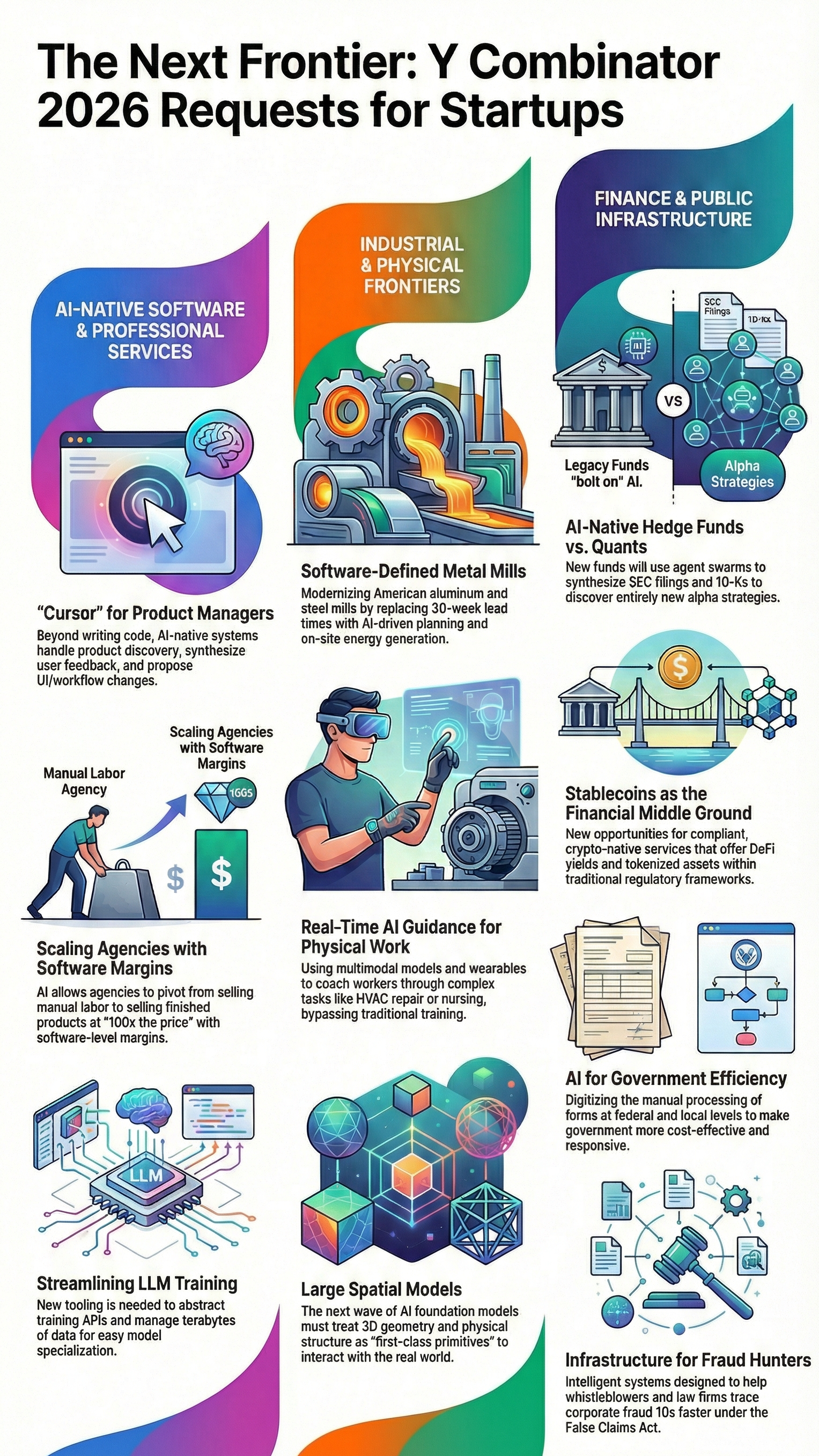

Y Combinator Requests for Startups 2026: Opportunities for Founders

Y Combinator Requests for Startups

Y Combinator's Requests for Startups represents a unique signal in the venture ecosystem. Unlike trend reports or market analyses, RFS outlines specific problems where YC partners and portfolio founders see structural opportunities for new companies. These aren't predictions about what might work—they're validated problem areas where experienced operators have identified gaps between what exists and what the market needs.

The Spring 2026 collection reflects a notable shift in how startups can be built. AI-native tooling has compressed development timelines and reduced capital requirements, enabling founders to tackle problems that would have required significantly larger teams just two years ago. The ideas span vertical AI applications, financial infrastructure, industrial modernization, and foundational model development. Each category represents a different risk-reward profile and requires distinct founder capabilities.

This analysis examines ten specific opportunity areas, exploring why existing solutions fall short, what makes the timing advantageous, and which founder profiles are best positioned to execute. The goal is to provide context for strategic decision-making, not to promote specific approaches.

What Makes YC Requests for Startups Different

RFS differs from typical startup idea lists in its source and intent. These opportunities come directly from investors and founders who spend significant time evaluating markets, talking to customers, and observing where incumbent solutions create friction. The list functions as pattern recognition at scale—distilling thousands of conversations into concrete problem statements.

Treating RFS as validation rather than instruction matters for founder psychology. The presence of an idea on this list suggests demand exists and sophisticated investors find the space credible. However, execution still determines outcomes. Domain expertise, technical capability, and distribution strategy matter more than alignment with a published framework.

The strategic value lies in understanding why these problems appear now rather than earlier. Timing signals often reveal technology shifts, regulatory changes, or market maturation that create windows for new entrants. Founders who can identify the underlying enabling conditions—not just the surface-level opportunity—gain strategic clarity about competitive positioning and go-to-market approach.

Cursor-like Tools for Product Management

Product development involves two distinct phases: determining what to build and implementing that vision. Recent advances in AI coding tools have dramatically accelerated the implementation phase. Engineers using Cursor or Claude Code can translate specifications into working software faster than previous generations could have imagined. This creates a bottleneck: the process of deciding what to build hasn't experienced similar acceleration.

Product management encompasses user research, market analysis, feedback synthesis, and prioritization decisions. Current workflows involve manual interview transcription, spreadsheet analysis, and subjective judgment about which features matter most. Teams use AI tools for isolated tasks—summarizing customer calls or analyzing survey data—but no integrated system supports the full discovery-to-specification loop. The artifacts produced—product requirement documents, design mockups, task tickets—were designed to communicate intent to human developers, not AI agents.

An AI-native product management system would ingest customer interviews, usage analytics, and market signals, then generate feature proposals with supporting evidence for why specific changes merit development resources. The system would translate product intent into specifications optimized for AI implementation: UI modifications, data model changes, and workflow adjustments broken into agent-executable tasks. This shifts product management from document creation to decision-making, with AI handling synthesis and translation.

The opportunity exists because the infrastructure prerequisites now exist at acceptable cost and quality. Multimodal models can process interview recordings, analytics dashboards, and design artifacts. Vector databases enable semantic search across customer feedback at scale. The broader adoption of AI coding tools creates market pull—teams who have accelerated implementation are now constrained by specification bottlenecks. Founders with product management experience combined with AI engineering capability can build systems that compress product discovery timelines from weeks to hours.

AI-Native Hedge Funds

Quantitative trading emerged in the 1980s when a small number of funds began using computers to identify market inefficiencies. The approach seemed unconventional compared to traditional fundamental analysis, but firms like Renaissance Technologies and D.E. Shaw demonstrated that systematic, data-driven strategies could generate consistent alpha. Today, quantitative methods dominate institutional trading. A similar transition is beginning with AI-native investment management.

Large asset managers have been slow to integrate modern AI capabilities into their core investment processes. Organizational inertia, compliance friction, and risk management frameworks designed for human traders create adoption barriers. Many firms experiment with AI for isolated tasks—earnings call transcription or sentiment analysis—but few have rebuilt their fundamental research and execution workflows around AI capabilities. This creates an opening for new entrants who design investment strategies specifically for AI execution rather than retrofitting AI onto human-designed processes.

An AI-native hedge fund would deploy agent systems to continuously analyze financial disclosures, earnings transcripts, regulatory filings, and market data. These agents would synthesize information across thousands of securities simultaneously, identifying patterns and anomalies that human analysts would miss due to bandwidth constraints. The fund's competitive advantage comes from strategy design optimized for AI execution: approaches that leverage computational scale, information synthesis speed, and the ability to process unstructured data sources that traditional quant models struggle to incorporate.

The timing is advantageous because model capabilities have crossed reliability thresholds for financial decision-making, while incumbents remain organizationally constrained. Founders need backgrounds in quantitative finance to understand strategy design, machine learning engineering to build robust agent systems, and risk management expertise to construct portfolios that survive market stress. The regulatory environment for algorithmic trading is established, reducing compliance uncertainty compared to genuinely novel financial products. The challenge is execution: building AI systems that generate alpha consistently rather than overfitting to historical data.

AI-Native Agencies and Service Businesses

Traditional service businesses face structural scaling limitations. Revenue grows linearly with headcount because delivering custom work for each client requires human expertise and time. Margins compress as firms add staff to meet demand, creating a ceiling on how large these businesses can become. Professional services—design, legal work, marketing, consulting—have resisted automation because clients value customized outputs that reflect their specific context and constraints.

AI changes the economics by enabling custom work at software-like marginal costs. A design agency using AI can generate dozens of visual concepts for a new client during the sales process, demonstrating capability before contract signing. A law firm can produce initial drafts of legal documents in minutes rather than billing weeks of associate time. An advertising agency can create multiple video ad variations without physical production costs. The key insight is that AI doesn't just speed up existing workflows—it enables entirely new business models where the service provider uses AI internally and sells finished deliverables at premium prices.

These AI-native agencies look more like software companies than traditional service businesses. Fixed costs go into building proprietary AI systems and workflows rather than recruiting large teams. Variable costs remain low because AI handles most production work. Margins approach software levels while retaining service business pricing power. The companies can scale revenue faster than traditional agencies because delivery doesn't require proportional headcount growth.

The opportunity is strongest in fragmented service markets where no dominant players exist and where outputs can be partially standardized while maintaining customization appearance. Founders need domain expertise in their target service vertical to understand client requirements and quality standards. Technical capability matters for building AI systems that reliably produce client-ready work rather than rough drafts requiring extensive human refinement. Go-to-market strategy is critical—these businesses sell outcomes rather than efficiency tools, requiring different positioning than software-as-a-service companies. The companies that execute well could consolidate fragmented markets by offering quality and speed combinations that traditional agencies cannot match.

Stablecoin-Based Financial Services

Stablecoins have evolved from experimental cryptocurrency instruments to functional components of global financial infrastructure. Daily transaction volumes rival major payment networks, and regulatory frameworks are crystallizing rather than remaining perpetually uncertain. Recent legislation in the United States establishes compliance requirements that place stablecoins between traditional finance and decentralized crypto markets—regulated enough for institutional adoption but retaining crypto-native efficiency benefits.

Existing financial products force users to choose between regulated offerings with limited returns and unregulated crypto with substantial risk. Regulated savings accounts offer minimal yield and slow cross-border transfers. Crypto yields come with smart contract risk and regulatory uncertainty. Stablecoin-based financial services can occupy the middle ground: products that provide better yields or access to tokenized real-world assets while operating under traditional compliance frameworks. This includes yield-bearing accounts, investment vehicles, and payment infrastructure that moves money faster and cheaper than correspondent banking networks.

The regulatory window is opening rather than closing. Policymakers have shifted from skepticism to framework development, creating predictability for startups building on stablecoin rails. The infrastructure is maturing—reliable stablecoin issuers, established on-ramps and off-ramps, and integration with traditional banking systems. Market demand exists from both businesses seeking payment efficiency and individuals wanting access to financial products unavailable through traditional institutions.

Founders need to understand both traditional financial services regulation and crypto-native infrastructure. Compliance expertise is non-negotiable—these companies must navigate banking regulations, securities law, and money transmission requirements. Technical capability in blockchain integration and smart contract security matters for building reliable systems. The business model requires balancing crypto efficiency with traditional finance trust and regulatory compliance. Success creates durable competitive advantages through regulatory moats and network effects, but failure modes include compliance violations and technical vulnerabilities that destroy trust irreversibly.

AI Tools for Government Operations

Government agencies process enormous volumes of forms, applications, and documentation, much of which still involves manual data entry and paper-based workflows. The first wave of AI consumer applications has increased form submission volume—individuals and businesses can complete applications faster using AI assistance. This creates a capacity crisis for government offices that receive these submissions and process them with legacy systems and manual workflows.

Agencies need AI tools that match the efficiency improvements individuals have gained. Automated document processing, intelligent routing, and AI-assisted decision-making could help government handle increased volume while improving responsiveness. The broader opportunity extends beyond form processing to making government operations more cost-effective and citizen-friendly. Countries like Estonia demonstrate what digital government can achieve, but most jurisdictions remain decades behind in technology adoption.

Selling to government presents significant challenges. Procurement processes are slow and bureaucratic. Security and privacy requirements exceed private sector standards. Decision-making involves multiple stakeholders with varying incentives. However, government customers also offer advantages once the initial sale succeeds. Contracts tend to be sticky with high switching costs. Expansion within an agency and across jurisdictions can reach substantial scale. Budget predictability exceeds many commercial markets.

The founder profile requires patience with enterprise sales cycles and comfort navigating regulatory and political complexity. Domain expertise in government operations helps identify high-value use cases and navigate procurement requirements. Technical capability in secure systems development is essential given data sensitivity. Go-to-market strategy should focus on specific agencies or workflows rather than attempting broad horizontal adoption. Success requires years of execution, but the market size and customer stickiness justify the investment for teams with appropriate capabilities and risk tolerance.

Modern Software-Defined Metal Mills

American metal manufacturing faces a structural problem that isn't primarily about labor costs or geopolitical considerations. Lead times for rolled aluminum and steel tube stretch from eight to thirty weeks, far longer than customer needs or competitive necessity. Most buyers cannot purchase directly from mills due to minimum order requirements and complexity. Despite high prices, mills operate on thin margins, suggesting systemic inefficiency rather than pricing power.

The root cause lies in production systems designed decades ago. Planning, scheduling, quoting, and execution remain fragmented. Mills optimize for tonnage and equipment utilization rather than delivery speed, flexibility, or profit margins. Short production runs and specification changes get treated as disruptions rather than opportunities to serve customers better. Automation has failed to address the workforce shortage because it focuses on pushing more volume through slow systems rather than eliminating setup time and variability.

Energy costs compound the problem. Aluminum and steel production consumes enormous electricity, but most mills rely on legacy power contracts and inflexible grid connections. On-site generation, sophisticated power management, and next-generation nuclear could dramatically reduce costs, yet mills rarely integrate new energy approaches into operations from the start. The combination of operational inefficiency and energy costs makes American metal uncompetitive on speed and sometimes on price despite proximity advantages.

Technology has reached the point where complete system redesign becomes feasible. AI-driven production planning can optimize for customer requirements rather than equipment utilization. Real-time manufacturing execution systems compress lead times by eliminating coordination friction. Modern automation reduces dependence on tribal knowledge held by experienced operators. New energy models can be designed into facilities from inception rather than retrofitted onto legacy systems. The opportunity is building modern, software-defined American mills—particularly in aluminum rolling and steel tube—where lead times and energy costs create the most acute pain. Success requires deep manufacturing expertise, software and AI capability, and capital to build physical facilities. The prize is rebuilding American industrial capacity with economics that make domestic production faster, cheaper, and more profitable than offshore alternatives.

AI Guidance for Physical and Field Work

Most AI application discussion focuses on knowledge work and which desk jobs face automation. Physical work—field services, manufacturing, healthcare—presents a different dynamic. AI cannot yet reliably act in the physical world, but it can see, reason, and guide humans who perform physical tasks. Real-time AI guidance systems could provide workers with expert-level support without requiring months or years of training.

The concept involves workers wearing cameras while AI observes their environment and provides verbal instructions: which valve to adjust, which tool to use, when components show wear requiring replacement. Instead of extensive apprenticeships or formal training programs, workers become effective immediately with AI coaching. The system accesses relevant expertise on-demand rather than requiring workers to internalize vast knowledge before becoming productive. This isn't about replacing human workers but about dramatically accelerating their capability development.

Three conditions have converged to make this practical. Multimodal AI models can now reliably see and reason about real-world situations in real-time. Hardware is ubiquitous—smartphones, wireless earbuds, and smart glasses provide adequate sensors and feedback mechanisms. Skilled labor shortages create economic urgency, making AI-augmented workforces attractive compared to unfilled positions or extended training programs.

Several business models could work. Building the guidance system and licensing it to companies with existing workforces offers broad applicability. Selecting a specific vertical like HVAC repair or nursing and building a complete augmented workforce creates defensibility through vertical integration. Creating a platform where individuals can acquire skills on-demand and start their own service businesses democratizes entrepreneurship in skilled trades. Founders need to understand the target vertical deeply enough to know what expertise matters and how to translate it into AI-deliverable guidance. Technical capability in multimodal AI and edge computing is essential. The biggest challenge is building systems that work reliably in diverse real-world conditions rather than controlled environments.

Large-Scale Spatial Reasoning Models

Language models have driven recent AI breakthroughs, but their impact concentrates in domains expressible primarily through text. The next capability frontier requires models that reason about spatial relationships, geometry, and physical structure as fundamental primitives rather than approximations layered onto language understanding. Current systems handle limited spatial tasks—basic object relationships or depth estimation—but cannot robustly reason about spatial manipulation, three-dimensional features, or operations like mental rotation.

This limitation constrains AI's ability to understand and interact with the physical world. Design, engineering, robotics, architecture, and manufacturing all require spatial reasoning that current language-centric models cannot reliably provide. A model that treats geometry and physical structure as first-class concepts could enable AI systems to reason about and design real-world objects and environments with the sophistication language models bring to text-based domains.

Building large-scale spatial reasoning models represents foundation model development rather than application layer work. The company that succeeds defines a new category of AI capability on the scale of OpenAI or Anthropic. This requires significant capital, exceptional research talent, and years of development before commercialization. The technical challenges include developing appropriate training approaches for spatial reasoning, creating or acquiring training datasets, and building inference systems that can handle the computational requirements.

The founder profile skews heavily toward research capability and ability to recruit top-tier AI talent. Prior work in computer vision, robotics, or computational geometry provides relevant intuition. Experience building and scaling large model training is essential given infrastructure requirements. This is not an opportunity for first-time founders or teams without deep AI research backgrounds. The timeline to commercialization exceeds typical startup horizons, requiring patient capital and tolerance for technical risk. Success creates a foundational technology that enables countless applications across physical industries.

Infrastructure for Government Fraud Detection

Government spending runs into the trillions annually across federal, state, and local levels, with fraud losses scaling proportionally. Medicare alone loses tens of billions yearly to improper payments. The False Claims Act's qui tam provision allows private citizens to file lawsuits on behalf of the government against companies committing fraud. Successful cases entitle whistleblowers to a percentage of recovered funds, creating financial incentives for fraud detection.

Current processes are painfully slow. An insider provides information to a law firm, which then spends months or years manually gathering documents and building the case. This should be dramatically accelerated with software. The opportunity is not building dashboards but intelligent systems that take insider tips and organize evidence: parsing complex documents, tracing corporate structures, and packaging findings into complaint-ready files. The software compresses investigation timelines from years to weeks or months.

Some startups are filing False Claims Act cases directly, but a larger opportunity exists building tools that accelerate whistleblower law firms, state attorneys general, and inspectors general. The market is substantial given the scale of government spending and fraud losses. Making fraud recovery ten times faster creates significant business value while returning billions to taxpayers.

Founder background is critical. Teams need members with direct experience in this domain—former False Claims Act counsel, compliance professionals, or auditors. Understanding investigation workflows and legal requirements is not something that can be learned quickly. Technical capability in document processing, entity resolution, and evidence management systems matters for building useful tools rather than feature demonstrations. The timing is favorable because AI capabilities finally enable automation of previously manual investigation work, and bipartisan political support exists for fraud reduction.

Tools That Make LLM Training Easier

Training large language models remains surprisingly difficult despite massive attention on AI development. Practitioners spend significant time on infrastructure problems: broken SDKs, unreliable GPU instances, bugs in open-source tooling, and managing terabytes of training data. The complexity creates barriers to entry and slows iteration for teams building custom models or fine-tuning existing ones.

The opportunity is building products that abstract training complexity: APIs that handle distributed training, databases optimized for very large datasets, and development environments designed specifically for machine learning research. As post-training and model specialization become more important, these tools could become foundational infrastructure for how AI-enabled software gets built. The tools enable more teams to train models and accelerate iteration for teams already training models.

Several approaches could work. Training abstraction APIs reduce infrastructure management burden. Specialized databases for machine learning datasets improve data pipeline efficiency. Development environments that integrate training, evaluation, and deployment workflows reduce context switching and improve productivity. The products serve teams building custom models rather than exclusively using pre-trained commercial models.

Founders need hands-on experience training models to understand where friction exists and what solutions provide genuine value. Building infrastructure for AI development requires both machine learning expertise and distributed systems engineering capability. The market timing is driven by increasing model training volume as more teams pursue custom models and fine-tuning. Success requires building tools that practicing researchers actually want to use rather than what theoretically should help. The challenge is creating sufficient value that teams will pay for infrastructure rather than continuing to build their own despite the inefficiency.

Cross-Cutting Themes Across All Ideas

Several patterns emerge across these opportunity areas. AI-native workflows represent a fundamental architectural shift rather than incremental improvement. The companies described don't add AI features to existing processes—they rebuild workflows assuming AI capabilities from the ground up. This creates performance differences that incumbents cannot match through feature additions.

Vertical-specific automation appears repeatedly. Rather than building horizontal tools applicable across industries, many opportunities involve deep specialization in particular domains. Success requires understanding industry-specific workflows, regulatory requirements, and quality standards. This creates defensibility through domain expertise barriers rather than pure technology advantages.

Infrastructure over applications shows up in several categories. Building foundational capabilities that enable many applications creates larger potential markets than individual use cases. However, infrastructure requires more capital and longer development timelines before revenue generation. Foundation model development, training infrastructure, and spatial reasoning capabilities all follow this pattern.

Regulatory and compliance advantages appear in financial services and government categories. Companies that successfully navigate complex regulatory environments build durable moats. Competitors cannot simply copy technology—they must also achieve compliance, creating time and expertise barriers to entry. These opportunities suit founders with relevant regulatory experience and patience for slower go-to-market timelines.

How Founders Can Use These Ideas Strategically

The value of Requests for Startups lies in validation signals rather than direction-setting. An idea appearing on this list suggests sophisticated investors find the problem space credible and believe demand exists. This reduces certain types of market risk and might facilitate fundraising conversations. However, execution still determines outcomes.

Independent validation matters more than alignment with published frameworks. Talking to potential customers, understanding why existing solutions fail, and identifying specific painful workflows provides more strategic clarity than matching RFS categories. The best startup ideas often combine elements from multiple opportunity areas or identify adjacent problems that published lists miss entirely.

Problem selection outweighs idea copying. Multiple teams will pursue each category, making differentiation essential. Founders with domain expertise, technical advantages, or distribution capabilities have better odds than teams attracted purely by investor validation. Understanding why a problem exists and what makes it solvable now provides strategic clarity that enables better decisions under uncertainty.

Execution risk varies dramatically across categories. Building AI guidance systems for physical work involves different challenges than developing foundation models for spatial reasoning. Capital requirements, timeline to revenue, founder background requirements, and risk profiles differ substantially. Matching founder capabilities to problem characteristics matters more than pursuing opportunities based solely on market size or validation signals.

Long-Term Relevance and Market Outlook

The opportunity areas described reflect structural shifts rather than temporary market conditions. AI-native workflows will continue displacing manual processes as model capabilities improve and costs decline. The specific applications will evolve, but the fundamental dynamic—rebuilding workflows around AI capabilities—persists beyond any particular year or funding cycle.

Financial infrastructure modernization follows technology adoption curves that span decades. Stablecoin-based services and payment systems represent early stages of a longer transition toward more efficient financial rails. Regulatory frameworks will continue evolving, but the direction toward crypto-native compliance appears established rather than speculative.

Industrial modernization and infrastructure development face physical and capital constraints that extend timelines beyond software-only businesses. Rebuilding American manufacturing capacity or developing new foundation models requires sustained effort over many years. These opportunities suit founders with long-term orientation and patience for delayed gratification.

The broader pattern is technology capabilities reaching thresholds where previously impossible or impractical solutions become viable. Understanding these threshold effects—why something works now but didn't three years ago—provides more durable insight than tracking which specific ideas appear on any particular list.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does working on a Request for Startups idea improve chances of getting into Y Combinator?

Working on an RFS idea provides validation that the problem space interests experienced investors, but it does not guarantee acceptance. YC funds hundreds of companies each batch, and most successful applicants work on ideas not listed in RFS. Execution quality, founder capabilities, and market timing matter more than alignment with published opportunity areas. The strongest applications demonstrate clear understanding of customer problems and early validation, regardless of whether the idea matches an RFS category.

How should founders approach RFS ideas if multiple teams are likely pursuing the same opportunity?

Competition within an opportunity category is inevitable. Differentiation comes from specific problem selection, unique insights about why existing solutions fail, technical advantages, distribution capabilities, or domain expertise. The founders who succeed typically identify specific customer segments or use cases within broader categories rather than attempting to build generic solutions. Understanding second-order problems—issues that become visible only after deep customer engagement—creates sustainable competitive advantages.

What distinguishes AI-native businesses from companies adding AI features to existing products?

AI-native businesses rebuild workflows assuming AI capabilities from inception rather than retrofitting AI onto processes designed for humans. The architectural difference creates performance gaps that incumbents cannot close through feature additions. AI-native product management tools, for example, don't just summarize customer feedback—they generate feature specifications optimized for AI implementation. AI-native hedge funds design investment strategies for agent execution rather than adapting human trading approaches. The distinction matters because it determines achievable performance levels and competitive sustainability.

Which RFS opportunities require the most capital to pursue?

Capital requirements vary dramatically. Foundation model development and modern metal mills require substantial capital—potentially hundreds of millions for facilities, equipment, and research infrastructure. AI-native agencies and product management tools can start with minimal capital, scaling as revenue grows. Stablecoin financial services need capital for regulatory compliance and reserve requirements. Government fraud detection infrastructure requires moderate capital for software development but minimal physical infrastructure. Founders should match their fundraising capabilities and risk tolerance to opportunity capital requirements.

How important is domain expertise versus technical capability for these opportunities?

The balance differs by category. Government fraud detection and modern metal mills require deep domain expertise—technical capability alone is insufficient. AI-native hedge funds need both quantitative finance knowledge and machine learning expertise. Product management tools and LLM training infrastructure weight technical capability more heavily, though product intuition still matters. AI guidance for physical work demands understanding the target vertical well enough to translate expertise into deliverable instructions. The strongest teams combine relevant domain experience with technical execution capability.

Can founders succeed pursuing RFS ideas without AI expertise?

Most Spring 2026 opportunities assume AI capabilities are foundational rather than supplementary. Founders without AI expertise face significant disadvantages in categories like spatial reasoning models, LLM training tools, or AI-native product management. However, some opportunities weight domain expertise more heavily—modern metal mills, government operations, or fraud detection could succeed with strong domain knowledge and partnerships for AI implementation. Founders should honestly assess whether their capabilities match opportunity requirements rather than forcing fit.

How do founders validate whether an RFS opportunity has genuine market demand?

Validation approaches parallel any startup: identify specific potential customers, understand their current workflows and pain points, and determine whether proposed solutions provide sufficient value to justify switching costs. The presence of an idea on RFS provides investor validation but not customer validation. Direct customer conversations, pilot projects, and early revenue provide stronger validation signals. Founders should be wary of building solutions that sound compelling to investors but lack demonstrated customer urgency.

What timeline should founders expect from starting work to achieving product-market fit?

Timelines vary substantially by opportunity type. Software products like AI-native agencies or product management tools might reach early product-market fit within 12 to 24 months. Infrastructure products serving developers could take 18 to 36 months. Government-focused opportunities face longer sales cycles—potentially 24 to 48 months before meaningful traction. Foundation model development and industrial projects might require three to five years before clear product-market fit. Founders should set expectations appropriately and ensure sufficient capital runway for their chosen category.

Are these opportunities relevant for founders outside the United States?

Several opportunities have explicit geographic considerations. Stablecoin financial services face different regulatory environments across jurisdictions. Modern metal mills address specific American manufacturing challenges but analogous opportunities exist in other countries. AI-native agencies, product management tools, and LLM training infrastructure are largely geography-agnostic. Government operations tools require understanding local procurement and regulatory requirements. Founders should evaluate whether opportunity assumptions hold in their target markets rather than assuming direct transferability.

How should founders think about competition from large technology companies in these spaces?

Large companies face organizational constraints that create windows for startups. Incumbent hedge funds struggle to adopt AI-native approaches due to compliance friction and cultural resistance. Established agencies cannot easily transition to AI-native models without cannibalizing existing revenue. Large technology companies building foundation models focus on general capabilities, leaving vertical specialization opportunities for startups. Government sales favor companies demonstrating domain expertise over general-purpose platforms. Founders should identify specific advantages—speed, focus, domain expertise, or business model innovation—rather than assuming large companies will ignore opportunities indefinitely.

Conclusion

Y Combinator's Spring 2026 Requests for Startups outlines specific problem areas where experienced investors and operators see structural opportunities. The collection spans AI applications, financial infrastructure, industrial systems, and foundational research. Each category represents distinct risk-reward profiles and requires different founder capabilities.

The strategic value lies in understanding timing signals and enabling conditions rather than treating these as instructions. Technology thresholds, regulatory changes, and market maturation create windows for new approaches. Founders who can identify why problems are solvable now—and build teams with appropriate domain expertise and technical capability—have advantages over those attracted purely by validation signals.

Thoughtful problem selection combined with strong execution creates outcomes. The opportunity landscape is broad, but success requires matching founder strengths to problem characteristics and building solutions that customers genuinely need rather than solutions that sound compelling in pitch meetings.