|

The hardest part of being a CEO

isn't designing the perfect

organization or setting flawless

objectives; it’s the psychological

struggle. It's the feeling you get

when you’re staring into the abyss,

forced to choose between two

horrible options.

This

is the world of

Ben Horowitz, co-founder of

Andreessen Horowitz

(A16Z), a venture capital firm with over

$46 billion in committed

capital, and the author of

The Hard Thing About Hard

Things. He has backed market-defining

companies from

Facebook and Stripe to Airbnb,

OpenAI, and Databricks.

|

|

Before launching A16Z, Horowitz

co-founded Loudcloud,

famously taking it public with just

$2 million in revenue, an

event often called

“the IPO from hell”, and

later sold it for

$1.6 billion. Through

near-death startup battles and years

of coaching hundreds of CEOs, he

forged a

management philosophy that defies

conventional wisdom, offering hard-earned insights on

leadership, scaling, and building

enduring companies.

|

|

|

|

In a recent podcast with

Lenny Rachistky

, Horowitz distilled the essential

mental frameworks required to

navigate the pain of leadership,

build world-class teams, and

understand the current AI landscape.

|

|

This isn’t a guide to management

techniques, it’s

Ben Horowitz’s High-Stakes

Leadership Playbook, a map for the psychological

gauntlet every leader must run.

|

|

In this post,

Ben shares:

|

-

Why

“founder

mode” is

both half

right and

half

dangerously

wrong

-

The story

behind

Good

Product

Manager/Bad

Product

Manager—and how it

went viral

despite

being

written in

anger

-

Where the

biggest AI

startup

opportunities

still

remain

-

Why

leaders

need to

run toward

fear,

never

away

-

The one

trait that

predicts

when a

founder

will fail

as CEO

-

Inside

Paid in

Full—his

nonprofit

that

provides

pensions to

pioneering

hip-hop

artists

|

|

|

The Psychology of a Leader: Why

Hesitation is Your Worst

Enemy

|

A. The Core Challenge: Running

Toward Fear

|

|

According to Horowitz, the single

worst mistake a leader can make is

to hesitate. This paralysis isn’t

born from easy choices; it comes

when you face two horrible

decisions, and every fiber of your

being wants to avoid both.

|

|

|

|

The essential psychological muscle a

leader must build is the ability to

look at those two awful options,

determine which is "slightly

better," and move forward

decisively.

|

|

Horowitz lived this principle when

he took his company public with only

$2 million in revenue. "That's

obviously a bad idea," he admits,

but the alternative was going

bankrupt, which was a worse idea.

|

|

|

|

He knew the press would call him

stupid—Business Week even ran

a story titled "The IPO from

Hell"—but moving forward was less

bad than the alternative. That

ability to run toward the pain is

what separates great leaders from

the rest.

|

B. Your Own Mind is the Biggest

Obstacle

|

|

Drawing on insights from his friend

Shaka Senghor, who survived 19 years in prison

and chronicled his transformation in

How To Be Free: A Proven

Guide to Escaping Life’s

Hidden Prisons, Horowitz makes a powerful point:

the harm you inflict on yourself

with your own beliefs is far greater

than any external pressure.

|

|

|

|

"All the things that you perceive

that are happening to you that are

bad... is very small compared to

like... if you believe it," he

explains.

|

|

For founders, this is critical. The

most common reason founding CEOs

fail is that they make inevitable,

high-impact mistakes, which causes

them to lose confidence.

|

|

That loss of confidence leads

directly to hesitation, creating a

power vacuum that invites internal

politics and dysfunction. A primary

role of A16Z is to help founders

maintain that confidence, because

your own psychology is the biggest

enemy you will face.

|

C. Success is an Accumulation

of Small, Hard Things

|

|

Success isn't a single stroke of

genius that gets written into a

triumphant narrative. Horowitz

learned from a pilot that plane

crashes are often a series of small,

individually manageable bad

decisions that compound into a

catastrophe. Success is the inverse.

|

|

It's

a series of small,

difficult-to-do things that

doesn't seem to have a high

impact, but leads to the next

small, hard-to-do thing,

eventually resulting in a

positive outcome. This slow

accumulation of navigating difficult

moments is the reality of building

something great.

|

The Counterintuitive Truths of

Building a Company

|

A. The True Value of a

Leader

|

|

A leader adds no value making a

decision everyone already agrees on;

the organization would have done

that without you.

|

|

A leader's only true value is

added when they make a difficult

decision that most people

dislike. This

requires telling people what they

don’t want to hear, which

they won't like in the short term.

But over the long run, that courage

is what saves the company.

|

|

|

B. "Managerial Leverage": Hire

People Who Make You Great

|

|

When

Ali Ghodsi, the CEO of

Databricks, was struggling to turn around

underperforming executives, Horowitz

gave him stark advice: "You don't

make people great. You find people

that make you great".

|

|

As a CEO, you aren't an expert in

every function, so the idea that you

can coach someone to be a

world-class marketer when you know

nothing about marketing is a dumb

idea.

|

|

|

|

True "managerial leverage" comes

from hiring world-class leaders who

bring ideas to you and push the

company forward. If you are the one

constantly pushing them and giving

them all the ideas, you have no

leverage. When you feel that

leverage is gone, you must make a

change.

|

C. Invest in Strength, Not Lack

of Weakness

|

|

When evaluating people, judge them

by what they do well, not by their

biggest mistake.

|

|

Horowitz points to A16Z's

controversial investment in

Adam Neumann

as a key example.

|

|

The world wanted to throw Neumann

away for his failures, but

Horowitz’s firm chose to focus on

his spectacular strengths.

|

|

The principle is to invest in a

person's world-class strength and

help them manage their weaknesses,

not discard them for being flawed.

"Everybody's uneven," Horowitz says.

Your job is to help them take their

strengths and use them.

|

D. The Product Manager as the

"Mini-CEO"

|

|

Horowitz stands by his famous "Good Product Manager, Bad

Product Manager" essay, clarifying that the PM

role is fundamentally a leadership

job that requires influence without

authority. He fully embraces the

"mini-CEO" analogy.

|

|

|

|

A CEO's job isn't to have every idea

but to consolidate good ideas, set a

vision, and align everyone to

achieve a goal. That is precisely

the function of a product manager.

It doesn’t matter if you write a

good spec; what matters is that the

product wins in the market.

|

Good Product Manager vs. Bad

Product Manager:

At a Glance

|

| Aspect |

Good Product Manager

|

Bad Product Manager

|

|

Ownership &

Mindset

|

Acts as the

CEO of the

product. Owns outcomes, defines

success, and takes full

responsibility for

delivering the right product

at the right time.

|

Looks for direction and

blames others (funding,

engineering, competition).

Measures effort instead of

results and makes excuses

when things go wrong.

|

|

Planning &

Execution

|

Knows the

market, product, product

line, and

competition

in depth. Devises and

executes a winning plan with

no excuses.

|

Starts without context and

lacks a clear plan. Expects

others to define the path.

|

|

Role with Teams

|

Manages the

product team and defines the

“what,” letting engineering

own the “how.” Avoids

getting bogged down in

project management or gopher

tasks.

|

Becomes part of the product

team, micro-manages the

“how,” and gets sucked into

day-to-day operational

noise.

|

|

Communication

|

Communicates

crisp requirements in

writing and

verbally. Documents positions on

key issues and sends regular

status reports on time.

|

Relies on informal, verbal

updates. Forgets or delays

status reports. Complains

when decisions don’t go

their way.

|

|

Marketing &

Positioning

|

Considers the

story for press and

analysts, asks smart questions, and

focuses on clarity over

technical minutiae.

|

Focuses on covering every

feature and technical

detail. Assumes press and

analysts “don’t get it.”

|

|

Customer & Revenue

Focus

|

Keeps team focused on

customers and revenue

goals. Defines products that can

be built and deliver value.

|

Focuses on competitors’

feature lists or impossible

products. Lets engineering

build whatever is most

technically challenging.

|

|

Problem-Solving

Approach

|

Decomposes problems,

anticipates flaws, and

builds real solutions

proactively.

|

Bundles problems together,

reacts late, and spends time

putting out fires.

|

|

Collaboration &

Materials

|

Creates reusable

collateral, FAQs,

presentations, and white

papers

to empower sales and

marketing.

|

Spends all day fielding

ad-hoc questions and

complains of being swamped.

|

|

Discipline &

Accountability

|

Defines their own role,

stays disciplined, and

consistently delivers.

|

Waits for instructions,

avoids accountability, and

lacks discipline.

|

|

Understanding the AI

Revolution

|

A. Why This Isn't a Bubble (The

Way You Think It Is)

|

|

While many are screaming "bubble,"

Horowitz argues this moment is

different from the dot-com era. Back

then, companies had no viable unit

economics. Today's AI companies have

products that work "so amazingly"

well and are generating massive,

real revenue growth.

|

|

The primary risk is not a lack of

value but potential

competitive displacement

as the very immature technology

evolves. The businesses are working;

the question is whether their

current positions are sustainable.

|

|

|

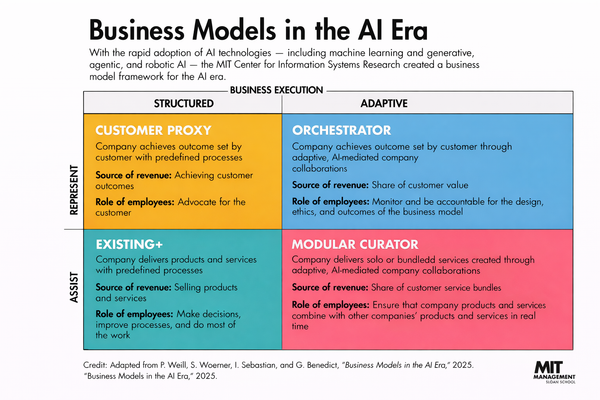

B. Where the Opportunity Lies

for Founders

|

-

Foundational Models:

Building these is incredibly

capital-intensive and limited

to a very small number of

founders who can raise at

least $2 billion.

-

Application Layer: This

is where enormous opportunity

exists. Horowitz dismisses the

"thin wrapper" narrative as

"really wrong". He points to

companies like Cursor, which

has built 14 different

specialized models to serve

developers, creating a

proprietary data moat through

user interaction. The problem

space is far larger than a

single foundational model can

solve, especially in the

enterprise, where issues like

data access control and

semantics are complex.

|

C. The Geopolitical Importance

of AI

|

|

Horowitz argues it is "fundamentally

important... to humanity" that the

United States leads in AI. Just as

industrialization determined global

economic and military power in the

20th century, AI will define it in

the 21st.

|

|

He believes the U.S. system of

decentralized power is the best

protector of individual opportunity

against authoritarian systems where

concentrated power has repeatedly

led to disaster. "We need you to

succeed," he says, quoting allies

from around the world.

|

|

Don’t miss this

Lenny Rachitsky podcast,

where

Ben Horowitz drops hard-won

lessons for founders.

Watch the video to catch the full

conversation.

|

|

|

$46B of hard

truths: Why

founders fail and

why you need to

run toward fear |

Ben Horowitz

(a16z)

|

|

|

Conclusion

|

|

Leadership is a psychological

battle, defined not by brilliance

but by the courage to make hard,

unpopular decisions. Success is

built on a foundation of investing

in people's strengths and

understanding that the path is one

of continuous, painful struggle.

|

|

Ultimately, how you feel about

yourself as a leader is paramount.

Horowitz’s parting advice serves as

a final, powerful lesson: "There's

no credit will be given for

predicting rain, only credit for

building an ark". It doesn't matter

if you predict failure; you still

failed. Your job is to build the ark

and find a way through the storm.

|